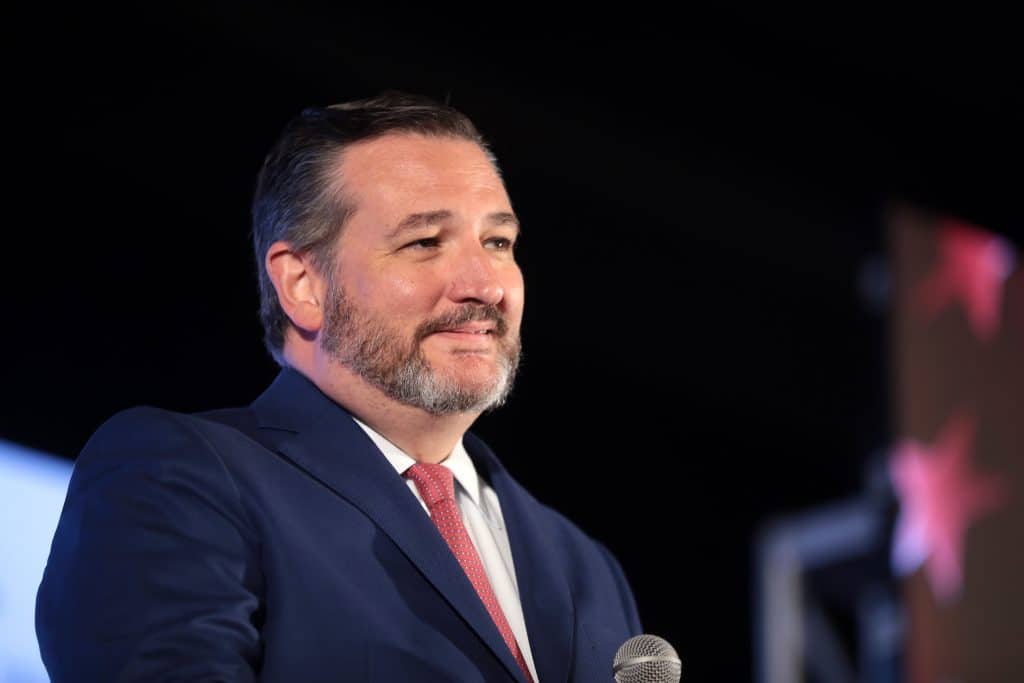

Photo: U.S. Senator Ted Cruz speaking with attendeesat the 2019 Teen Student Action Summit in Washington, D.C./Gage Skidmore

McCain-Feingold, the campaign-finance legislation adopted by Congress in 2002, includes several provisions (known collectively as “the Millionaires’ Amendment”) designed to protect incumbent members of Congress facing very wealthy challengers. Among the provisions is one that limits a campaign committee’s right to use funds raised after the election to repay large loans (in excess of $250,000) made to the committee by the candidate himself.

The Supreme Court has agreed to hear a challenge to the loan-repayment limitation brought by Texas Senator Ted Cruz, FEC v. Ted Cruz for Senate. He and others allege that the limitation, 52 U.S.C. § 30116(j), improperly burdens a congressional candidate’s First Amendment right to spend his own money advocating his own election. The case was argued in the Supreme Court this week. But federal officials defending the law are doing all they can to prevent the Court from ever reaching the First Amendment issue; they argue that Senator Cruz lacks “standing” to challenge the limitation. The Court should reject that procedural ploy; if accepted, it would seriously impair the ability of plaintiffs to challenge unconstitutional government action.

The Standing Requirement

“Standing” is a well-accepted limitation on the power of federal courts to decide matters brought before them. A belief that a law is improper does not suffice to permit one to file a federal-court challenge to the law. Rather, to demonstrate standing to sue, a plaintiff must show that he has suffered an injury directly traceable to the challenged law, and that the relief he requests would remedy his injury. The standing requirement ensures that the parties before the court have adverse interests and thus that the arguments on both sides of the case will be well developed.

The Federal Election Commission (FEC), which is defending the loan-repayment limitation, concedes that Senator Cruz has suffered an injury—he has been repaid only $250,000 of the $260,000 he loaned to his campaign committee. But it argues that Cruz lacks standing because, it alleges, his injury is not “directly traceable” to § 30116(j). Rather, it argues, the injury is attributable to a regulation FEC issued for purposes of implementing the statute, and (for highly technical reasons) Cruz is not permitted to challenge the regulation directly. If FEC prevails on its standing argument, the Supreme Court will rule against Senator Cruz without ever addressing the merits of his First Amendment claims.

A Major Roadblock to Constitutional Challenges

NCLA has taken no position on the First Amendment claim raised by Senator Cruz. But as spelled out in an amicus curiae brief it filed with the Supreme Court, it strongly opposes FEC’s standing argument, which it views as a dangerous attempt by the Executive Branch to block challenges to unconstitutional government action.

Section 30116(j) only limits loan repayments using campaign funds raised after the election; campaign committees may use an unlimited amount of pre-election contributions to repay candidate loans. The impediment to full repayment of Senator Cruz’s loan arose not because his committee lacked sufficient pre-election contributions to repay the loan. Rather, the impediment arose because Senator Cruz waited more than 20 days after his 2018 re-election to request repayment. And an FEC regulation declares that all pre-election contributions should be reclassified as post-election contributions on the 20th day following the election. That reclassification left the campaign committee with only post-election contributions in its bank account, and (under the challenged statute) only $250,000 of those funds could be used to repay the candidate loan.

Under any plausible interpretation of the term, Senator Cruz’s injury is “fairly traceable” to § 30116(j), the challenged statute. But for § 30116(j), FEC would not have issued the 20-day regulation; indeed, it would not have had authority to do so. The regulation’s existence as an intervening step in the causal chain does not prevent Senator Cruz’s $10,000 loss from being “fairly traceable” to the statute. He thus has standing to challenge the statute.

FEC is asking the Supreme Court to adopt a new, heightened standard for establishing that an injury is directly traceable to complained-of conduct. It asserts, without any support in existing case law, that a plaintiff lacks standing to challenge an allegedly unconstitutional statute when his injury is most directly attributable to an agency regulation adopted to implement the challenged statute rather than to the statute itself. FEC’s proposed heightened standard would significantly restrict challenges to unlawful government action, challenges of the sort that NCLA is dedicated to raising.

For example, NCLA has frequently challenged statutes by which Congress has delegated its legislative powers to Executive Branch agencies, in violation of the Constitution’s mandate that legislative power be exercised by Congress alone. Under FEC’s proposed standard, NCLA would lack standing to bring all such claims. Congress’s adoption of a statute that divests its legislative power does not directly inflict injury; the legislation merely invites a federal agency to exercise open-ended, delegated legislative powers. Only when the agency begins to exercise those unlawful powers by adopting regulations do individuals incur injuries. Under FEC’s heightened standard, those individuals would lack standing to challenge the underlying statute as a violation of Article I, § 1 (which vests legislative power in Congress alone) because (according to FEC) their injuries are “fairly traceable” only to the agency regulations, not to the unconstitutional statute that authorized the regulation.

If individual citizens are to continue to be afforded a right to redress their constitutional injuries, the Court must reject FEC’s efforts to bar the courthouse doors.

Self-Inflicted Injuries

FEC also argues that Senator Cruz’s $10,000 injury is not traceable to the statutory loan-repayment limit because it was in some sense “self-inflicted.” FEC notes that Cruz intentionally delayed seeking the loan repayment precisely because he wanted to test § 30116(j)’s constitutionality.

But the Supreme Court has never denied standing to litigants who purposely incur an avoidable injury because they seek to challenge the constitutionality of the law that injured them. When an individual searches for and finds a violation of the law, it is the violation itself—not the search—that causes the plaintiff injury. Were it otherwise, Rosa Parks would have had no basis for challenging her denial of a seat on the Montgomery, Alabama, bus because she could have avoided all trouble if she had not boarded the bus for the purpose of instigating litigation. Intentionally violating a law for the purpose of challenging its constitutionality has been a keystone of efforts to protect constitutional rights since at least Plessy v. Ferguson, the infamous 1896 separate-but-equal Supreme Court decision.

In sum, the Supreme Court should reject FEC’s efforts to prevent constitutional challenges to its conduct. Senator Cruz is entitled to have his First Amendment claims addressed on the merits.