How the Administrative State Spawned the Granddaddy of All Patriotic Holidays

Patriots Day—the granddaddy of all patriotic holidays—is today, April 19th . While it deserves national recognition, it is an official holiday in only four states. In Massachusetts, Patriots Day is observed on the third Monday in April and it is celebrated with the running of the Boston Marathon, a morning Red Sox game at Fenway Park, and Revolutionary War battle reenactments. Growing up in the Berkshires, it was one of my favorite holidays—a patriotic-themed harbinger of summer. But if you don’t live in New England, you might not be familiar with Patriots Day.

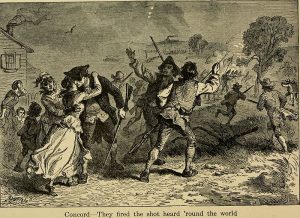

The holiday commemorates the Battles of Lexington and Concord and the start of the American Revolution—what Ralph Waldo Emerson called “the shot heard round the world.” What could have caused a bunch of New England farmers, tradesmen, and merchants to get so riled up that they were willing to confront an elite expeditionary force on the battlefield? It was the Administrative State’s disregard for their civil liberties.

Loose Lips Sink Ships

The British pre-dawn raid had been planned many weeks prior to April 19, 1775. The scheme was clean and simple—sneak 700 soldiers out of Boston under the cover of darkness, march 17 miles northwest to Concord, Massachusetts, and seize the Patriot arsenal at dawn. A total surprise. No muss, no fuss. Easy peasy. What could go wrong?

Well, for starters, a surprise attack will only surprise its target if secret orders are kept secret. Redcoats, secret orders, and alcohol apparently don’t mix, because everyone knew the raid was coming. Bostonians had been carousing in their pubs right alongside the British for several weeks prior to the “secret” raid, so the arsenal at Concord had been long emptied by the morning of the 19th.

In fact, the tables were turned on the British at about 5:00 a.m., roughly 10 miles into their march. About 70 Patriot militiamen surprised the Redcoats on the Lexington town green. Seven miles up the road, the British discovered that the Concord arsenal was empty, so they searched every structure in the town, seized anything that could be put to military use, and burned it in a massive (and unruly) bonfire. By this time, 400 Patriot militiamen had gathered on the high ground outside of town, and fearing that the British were going to burn the town to the ground, descended on a company of 100 Redcoats at the Old North Bridge. Once again surprised (but this time, also outnumbered), the Redcoats retreated to the main body of the British forces just outside of town.

The British began a tactical retreat to Boston, but their problems were just beginning. Throughout the morning, Patriots had been gathering—by some reports, as many as 5,000 by the early afternoon. The militiamen engaged the retreating column from behind every rock and every tree along the 17-mile path back to Boston.

British Bureaucrats Began Sowing the Seeds of Rebellion in 1760

The anger that led to the shots at Lexington and Concord had been long-festering. Merchant marines in Boston frequently engaged in smuggling when trading with the West Indies, to avoid British taxes. During the French and Indian War (1754-1763), though, this smuggling not only diminished British tax revenue needed to finance the war, but the substantial illicit trade between Boston and the West Indies kept the French war machine afloat in the New World.

This posed a very serious problem for the British, so they authorized customs officials to execute general warrants—called writs of assistance—permitting them to board any ship or enter any structure to search for and seize smuggled goods without any showing greater than rank curiosity. James Otis contemporaneously described the writs as “the worst instrument of arbitrary power[.]”

Not surprisingly, writ-happy bureaucrats armed with open-ended general warrants harassed a lot of colonists. The warrants were not issued by a judge on sworn evidence of probable cause—judges perfunctorily issued writs when requested by customs officials without any judicial oversight. The writ authority was often abused which led to some very hard feelings between the colonists and the crown.

The cherry on top of this Rebellion Sundae was the Intolerable Acts of 1774 which, among other things, closed Boston Harbor and reinstated royal governance, which pushed Bostonians over the edge. In response, Massachusetts formed the Massachusetts Provincial Congress on October 7, 1774. Then, on February 9, 1775, Parliament declared Massachusetts in rebellion. In other words, game-on—the Battles of Lexington and Concord were inevitable.

Celebrate and Appreciate Patriots Day

Patriots Day is the granddaddy of all patriotic holidays. Without it, there wouldn’t be an Independence Day, Abraham Lincoln couldn’t have issued a presidential proclamation establishing Thanksgiving, and there wouldn’t be a need for Memorial or Veterans Days.

We celebrate Patriots Day to commemorate the start of the American Revolution and to honor the courageous militiamen who fought. But we should also take time to appreciate the liberty-preserving principles of the Constitution borne out of the causes of Patriots Day. In particular, the prohibition against general warrants such as writs of assistance.

As Prof. Philip Hamburger observed in his book Is Administrative Law Unlawful?, the “response of [colonial] Americans to the writs of assistance thus reveals how systematically the U.S. Constitution barred any return to administrative orders and warrants.” The Constitution, Prof. Hamburger explained, places judicial power in the courts—all binding orders and warrants come from judges, whose role it is to protect the right to due process of law.

But we must remain vigilant to ensure that the Founders’ struggle to overcome the writs of assistance was not in vain. Indeed, despite the Fourth Amendment, we see a resurgence of the functional equivalent of general warrants in modern day America. Courts abdicate their judicial responsibility to protect our civil liberties when they permit agencies operating under open-ended inspection statutes to exercise the agency’s discretion to enter onto private property for examination. In some circumstances, courts will review administrative warrant requests, but judges will issue the warrants on showings of less than probable cause—in essence, fishing expeditions that sound an awful lot like writs of assistance.

The good news is that we aren’t 18th century colonists and we have a Constitution that already prohibits this judicial deference to administrative action. The New Civil Liberties Alliance is committed to restoring the Constitution’s particularized warrant scheme—indeed, NCLA is committed to protecting all Americans’ civil liberties—by bringing original litigation in state and federal courts, to hold the administrative state and the judiciary accountable when they stray from the constitutional order.

There’s one more thing to keep in mind on Patriots Day: The next time an obnoxious Boston sports fan annoys you because the New England Patriots have won another Super Bowl or the Boston Red Sox have won another World Series, just remember that if it wasn’t for us hot-heads in New England, you might still be a British subject! You’re welcome.